“Join me at the banquet of rational thought and creative expression; in the dance of the material and mystical; through the kaleidoscope of perception; to understanding and compassion for the self and society.”

San Francisco State University. Gymnasium 115, HUM 220-03. Wednesday, May 4th, 2022, 3.50 pm

Meet Marie

Entering the room, a faint scent of flowers and consumed memories fills the secluded space of the university building. A comforting warmth seems to fill every corner. Behind the table stands a woman, her eyes and hands engaged in navigating reams of paper and letters inked across sheets marked with ink, ironically disordered by her continuous efforts to arrange the pages.

Despite her meticulous focus on every word and detail of the prints, she never fails to lift her head as soon as someone enters the room, accompanying a warm smile with a kind and encouraging “welcome”. A coloured vest brightens her face, while her eyes shine softly behind the simple frame of her eyeglasses.

As soon as the hour clocks, Marie finally looks up at her students, counting with her eyes how many pupils will attend her class this year. A smile starts the first lesson of the semester. “Welcome to my ‘Values and Culture’ class. My name is Marie Thomas McNaughan, but you can simply call me Marie. It’s a pleasure to have you here with me today and for this semester. How are you?“

Versatility as a solution

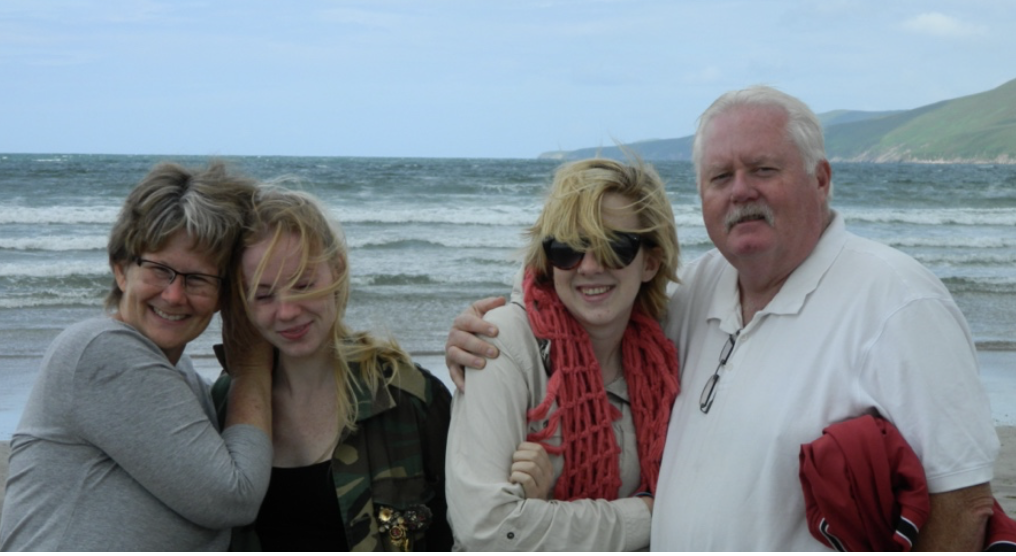

Marie Thomas McNaughton is 66 years old, she was born in the northern side of the Bay Area and currently lives in California in the Wine County. She’s “mostly retired” – which means she does “the things I’ve always done but I don’t get paid for them,” she affirms ironically.

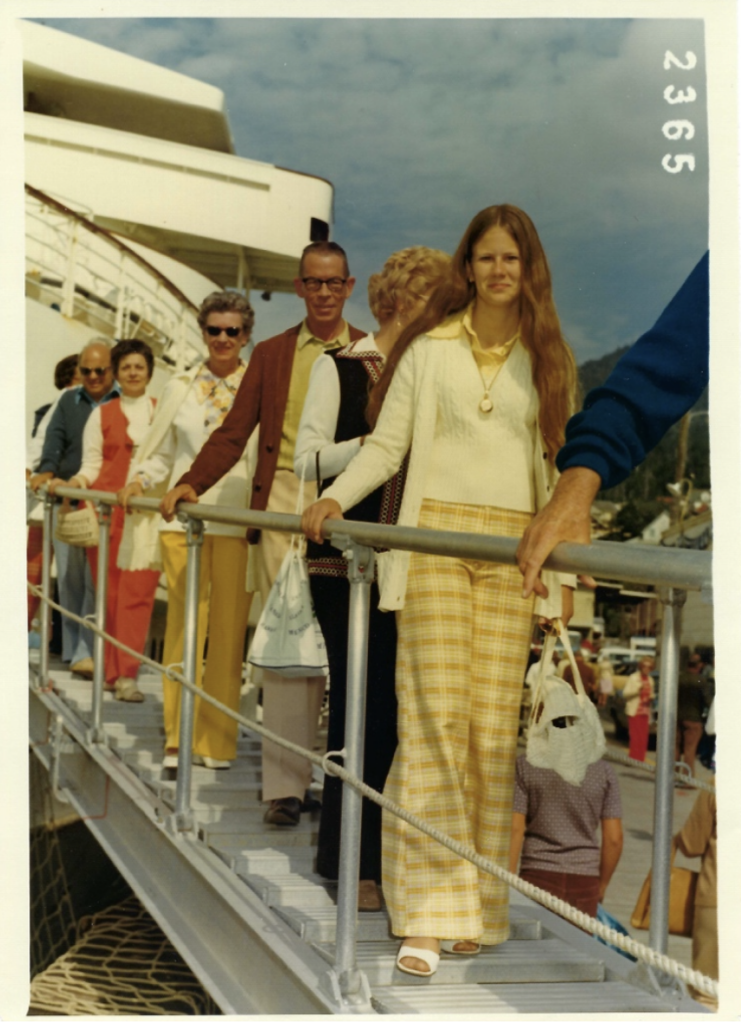

Marie has the ability to pair words with elegance and precision, taking her time to find the ones that suit the context best. Empathetic and warm, all her movements scream patience and interest for the other to find their place in the world. After graduating college in British literature, throughout her youth she worked in different environments, switching jobs and sectors thanks to her passion and interest for the world around her. She started her career researching, writing, and providing photography for local, national, and international news and features, then traveling extensively for The Goldsmith. As the time went on she went to write, edit and coordinate for the San Francisco Magazine and for the San Francisco Review of Books.

“My curiosity was my motor, allowing me to get acquainted with one job or another. I was always ready to learn something new and practice a new job.”

Women can study science, too

Marie soon understood the importance of setting herself on the same level as her male peers. Understanding the limits in the comparison, she filled her lack with her curiosity.

It was hard because at the beginning I didn’t have a background in science. Back then, if you had a free class, they would’ve pushed you to take a “female class” – French literature, for example… Hence, I had no experience in science.

To understand scientific method, for example, she became a docent at the SF zoo, aiming to learn zoology and ways of analysing animal behaviour and bringing that knowledge to the public.

After her career in advertising came to a conclusion, Marie ended up going to school at night, finally teaching humanities at SFSU.

Students had to take my class without them being really interested in. I had to find ways to open boxes, different boxes. I was word smart, nature smart. I had to teach to people who were body smart, and I had to modify my class for them to embrace and understand what would’ve otherwise been just words. To enhance their senses of humanity.

A journalist is a photographer: the psychology behind journalism

Since she was young, Marie has loved doing profiles of people, scrutinare la loro persona e personalità e renderle interessanti per il grande pubblico. Growing up, she used to constantly virtually interview people, treating their stories as pieces. It was like taking a picture of their personalities through her words, making them interesting and putting their word out.

Trying to be rational and objective rather than making an emotional connection with people was definitely a way to protecting herself. Marie has always been shy and at one point even had social anxiety, and she often put on this social interviewer persona to help herself. Moreover, putting her subject in focus meant that she could hide behind the camera.

Back then I felt safer and it felt intimate, although it was well closer to being the opposite of that. I was very task oriented, looking for details that could create a connection between me and my subject. But when I thought I was being interpersonal, I was rather intrapersonal.

As she grew up, studying philosophy and sociology as well as starting a family, she got to understand the reasons behind her actions.

As we move along life, we look at it differently. I was curious, and not only towards others, but also towards myself.

Writing with a purpose

For Marie, writing always came with a personal return. Every time she got to write about something, she could learn about it first. In fact, her passion was going into a topic with little to no information and coming out with a piece that everybody could understand, without the jargon and the details.

That was my favorite part of being a writer for magazines: learning about something I didn’t know. I was always learning. Always.

Writing about Native Americans

My family has always spoken of a myth stating that we had Indigenous roots. For as long as I can remember, both my father and I had believed it to be true.

Born and raised in the Marin and southern Sonoma Counties, since she was a child Marie has always loved wandering around the firm and dark, wet and grassy stretch of land that are the Woodland and Red Wood Forests, discovering and embracing their vegetation and wildlife step after step. During her long, solitary walks, peeking inside the local Native Americans reserve hoping to grasp a crumb of the culture that for so long had kept her on her toes, Marie has always felt a connection to the local Indigenous communities.

I was always in and out of it, and the land called to me.

As soon as she got the chance, Marie started deepening her interest in the local indigenous culture, exploring the world of tribe of Native Americans with a focus on the Cherokee Tribe.

The Cherokee Tribe

Today, the Cherokee Nation is the largest tribe in the United States with more than 450,000 tribal citizens worldwide. More than 141,000 Cherokee Nation citizens reside within the tribe’s reservation boundaries in northeastern Oklahoma [Cherokee.org].

The members of the Cherokee tribe are quite dispersed all over the American soil, so much so that many believe they have traces of Cherokee heritages in their blood.

The Cherokee Tribe is committed to preserve and teach their culture, unique under many points of views.

The members of the community speak the Cherokee or Tsalagi language (ᏣᎳᎩ ᎦᏬᏂᎯᏍᏗ). To protect the language, the Cherokee Nation Language Department was created, and is now committed to preserving and perpetuating the language through day to day spoken use and by generating more proficient second-language Cherokee speakers.

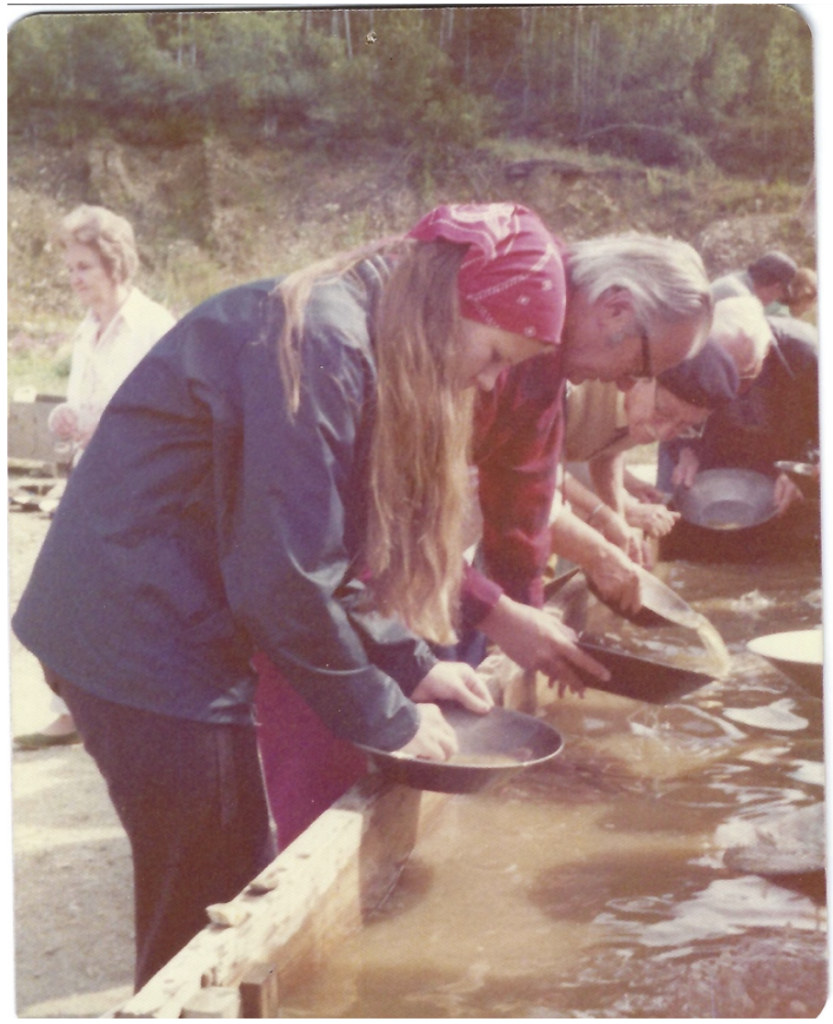

Besides their language, many other aspects of the Cherokee culture are preserved and, what’s more, taught. This is in fact the way Marie could get a chance to approach and discover the culture through a practical and direct experience, practicing traditions through her body. These experiences included the creation of baskets as well as of the traditional tule canoe or tule reed boat, embraced by Northern California tribes such as the Coast Miwok, Ohlone, and Pomo for thousands of years [Visit California].

Thanks to members of the community who, despite their anger and pain for their past, decided to divulge and share their culture through courses and direct experiences before their traditions either fades, or worse, gets taken away from them, Marie could learn how to become part of the community although considered an outsider.

The value and potential future life of indigenous people is entwined and connected with my desire of being an educator. I feel called to live out what was a pretend connection that’s real for me and who I see myself as. I don’t want to be ignorant about the people that were living this lands before me: I want to be the bridge between them and those who are unaware of their culture and history.

How do you get trusted by indigenous communities?

I took multiple and different DNA tests to verify this myth, but sadly they all proved me to be, in fact, not part of the community.

Despite finding out her connection to the Cherokee tribe was only a made up story, Marie decided to continue digging into the culture of a community she felt spiritually connected to, and spreading the story of an endangered land she desired to protect and highlight.

However, despite her attempts and even potential success, Marie was conscious that to the Native American eyes will always be an oppressor to the indigenous people she interacts with.

I’m not a native and I will never be. This means that, despite how I pose myself, I will always be an oppressor for them. As a white person, I will forever be one of their oppressors.

Getting in contact with the local Indigenous community has in fact proved to be complicated, delicate and unsure. Given the past, indigenous tribes have always reserved anger and suspicion to all the people looking inside their space, showing a conscious unwillingness to trust.

Unable to fight or surpass this sentiment built through the years, Marie had to find her way inside the community, step by step proving locals to be a trustable external source.

Nowadays people are more willing to express their anger and dismay to what has happened to their land and people.

It possible to share and divulge a culture as an outsider

“The western concept of time is very linear: there’s a past that is distinct from the present as well as from the future. Differently, for indigenous communities, time is an illusion: everything is a circle and a cycle, and we live in the present, past and future at the same time. I had to learn patience, and that the concept of deadlines is contrary to how indigenous people see the passing of time.”

Things will circle around to that moment when it’s the right time for me to get accepted in their community despite not being part of it. Only then I will be able to fully be a disseminator of their culture.

Could be an outsider be a tool to connect better with other outsiders and colonisers.

Marie however decided to embrace her perspective. She, in fact, considered herself a witness. In this sense, she witnesses the experience of indigenous people from the point of view as an outsider, and then, through the authority she gained by being a teacher and educator, she decided to use her voice to create compassion and partnership and connect better to those who wouldn’t be able to interact directly with the culture itself (as a bridge as long as done with humility and with the permission of indigenous people).

Discussing the life of indigenous people, Marie underlines the importance of small steps that are necessary to acknowledge the past and culture of native Americans. One of these is Land acknowledgement by the introduction of the place the writer or scientist is studying and portraying, stating the Native land one’s talking about. In this way, it is possible to acknowledge that this land used to belong to somebody else and that it was later taken over, bringing natives to lose their control over it.

And objectivity, if reachable, isn’t useful. She’s a witness, and witnesses things.

Marie however fear the impact of climate change on the life of indigenous people.

If we continue this way, there won’t be a place for them to regain, neither one where we can even try to cooperate.

Appreciation or appropriation?

These increased the appreciation. What’s different between appreciation and appropriation is the bigger question. In her mind education creates growth and connection (ignorance bliss bit), thus allowing connection with each other and the land

Is there a “we” that includes both indigenous and non-indigenous people?

Is it possible to give back to African Americans and indigenous people? Virtually or physically? What would help us give something back to them? And what do they do in the rest of the country?

Is there a verifiable reality? Marie’s relation with technology

Some students never got to enjoy the world around them. I blame technology for that, it locks you in a bubble that’s hard to escape. Technology helped connecting people through pandemic, and it’s ironic to think about how it is tearing our reality apart now. You gotta get out there, it’s not enough to have a virtual reality.

The (control) of media and misinformation

Alongside the problems concerning technology come the ones about misinformation. In the eyes of a teacher and journalist, Marie thinks the problem is incredibly dangerous and frightening.

The world is so polarised due to algorithms that create these echo chambers where we keep getting the same information over and over again since we’ve been there again, instead of having the multiplicity of voices.

While discussing the problem, she struggled finding her words. “My vocabulary is not supporting me now, maybe because this problem frightens me a lot, and impacts my mental abilities and coherence” she wonders.

As a journalist, recognising the existence of this new form of “journalism” was painful. Throughout her career, Marie tried to portray and share the so called “accurate, objective, verifiable, citable” information. Even when debating, she has always searched for a way to answer with pieces of information “as true as they can be.” People had called her a liar multiple times since, spreading what she calls misinformation and unsupported claims instead.

Is knowledge worth the awareness? A reflection on Thomas Gray’s 1742 Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College

Despite the pain implied in awareness, Marie would never give up knowledge.

“Sometimes people reference Thomas Gray’s 1742 poem Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College‘s quote

“No more; where ignorance is bliss,

‘Tis folly to be wise.“

Gray was referencing and playfully inverting the conclusion of an important verse:

For with much wisdom comes much sorrow; the more knowledge, the more grief.

Sure, that is where everyone stops. It’s a global misunderstandings. That was only Gray’s answer to the original Ecclesiastes, but in response he did receive one more letter by King David that changes everything:

“Then I turned my thoughts to consider wisdom, and also madness and folly. What more can the king’s successor do than what has already been done?

I saw that wisdom is better than folly, just as light is better than darkness.“

The point is where you set yourself. I’d never, ever give up awareness for a simpler life – it would be simpler, sure, but not better. Once again, it proves that one decides to listen not only what ever served in their echo chamber, but also that people see only what they want to see.

“What’s most important: Awareness leads to acceptance, which sets foundations to actions.”

Marie today: her impact on her community

I am a person who knows how to love, who devotes his time to others to give back to the community what the community has given me.

Today Marie “researches, writes, speaks, talks, discusses books, teaches, reads, participates in the local historical community, helps people network and gets them where they want to get.“

In her little free time she takes part in parades in the name of historical community. She loves the idea of getting people excited of history, of their past. She loves to address kids and tell them they’re making history by taking part in an historical event. She thinks many people don’t realise how much happened before they arrived on this world. She wants to find ways to find that interesting. Interested about the history of their community. Maybe some parents aren’t telling them where they come from, so I help them see the beauty of their past. And she shares her, which might help them share theirs or understand theirs – as a journalist, I’ve done that a lot, which may or may not have worked – to let people feel comfortable in their stories and appreciate their quotidian through our words.

I understand the rational and the passionate and I want to be the bridge between the two. I came to the conclusion that to be (occasionally) wise you have to be both.